Birds have disappeared from the agricultural landscape

The population of fieldfare in the agricultural landscape has declined by as much as 56 percent over the period 2000–2023. Photo: Christian Pedersen

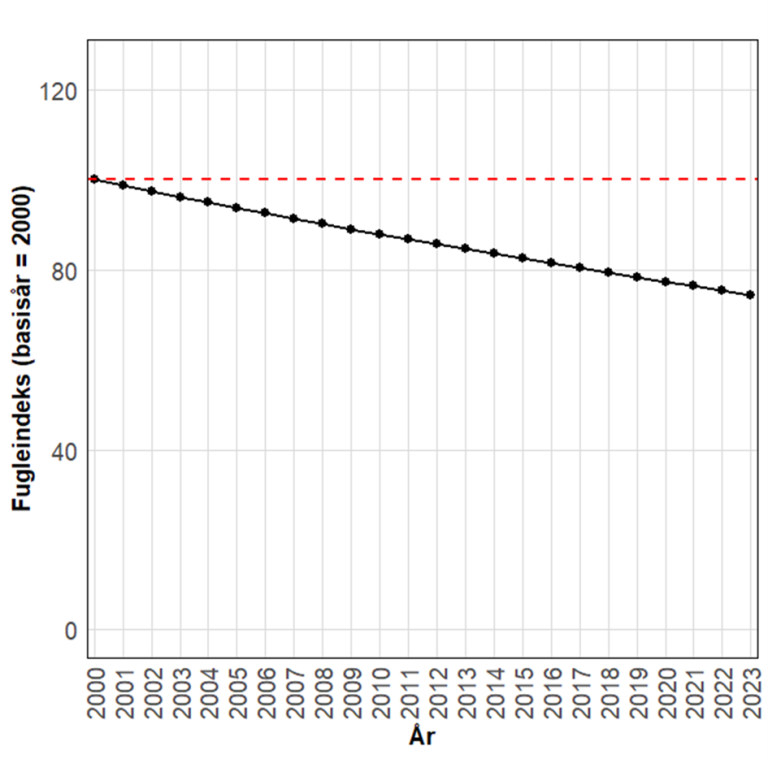

New figures from NIBIO’s 3Q programme show that the total population of farmland birds has declined by about 25 percent since the turn of the millennium. The trend highlights the need for targeted measures to preserve a diverse and bird-friendly agricultural landscape.

In Europe, it is well documented that bird species associated with agricultural landscapes have experienced a sharp decline over several decades. Since 1980, populations have been reduced by around 60 percent. New Norwegian figures show that the same negative trend is also evident in Norway.

The bird index shows a decline for many species

The “Norwegian monitoring programme for agricultural landscapes” commonly known as 3Q, has been run by NIBIO since 1998. Among other things, the programme tracks land use, landscape changes, and how these affect biodiversity.

“We have monitored breeding birds in the agricultural landscape for 25 years,” says NIBIO researcher Christian Pedersen. To summarise the results, the researchers have calculated a dedicated bird index.

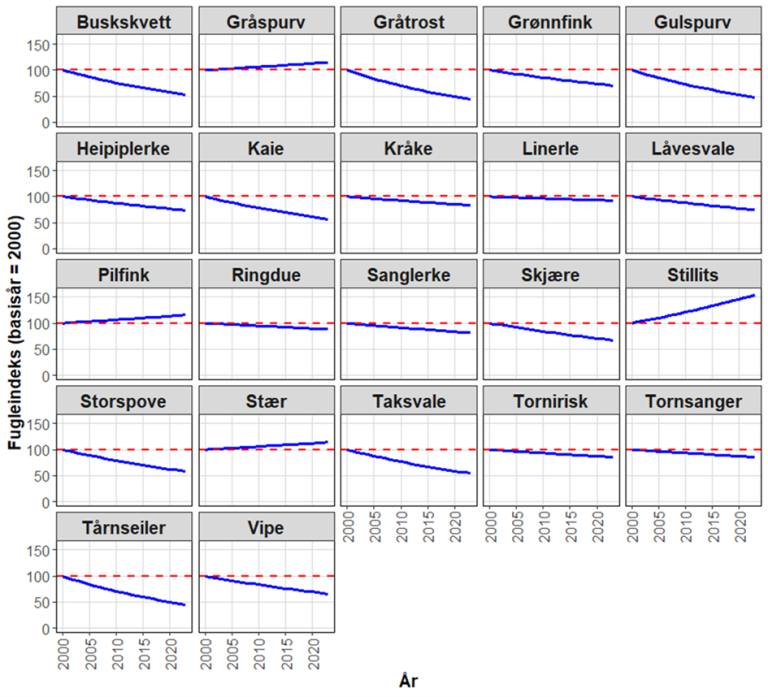

In total, there are around 34 species that live mainly in agricultural landscapes—so-called farmland birds. Not all are equally common or widely distributed. The researchers have therefore selected the 22 species that are common enough to provide a reliable picture of trends over time.

Since the 3Q monitoring began in 2000, this year serves as the reference point (index value = 100). Since then, the results show a steady and clear decline throughout the period. In 2023, the bird index had fallen to around 75—a reduction of approximately 25 percent since monitoring began.

Some species are increasing, but most are declining

Pedersen explains that there is some variation between species, but several common species have experienced particularly strong declines.

“The fieldfare has declined by as much as 56 percent, while populations of the common swift, yellowhammer, and whinchat have been reduced by around 50 percent. At the same time, some species, such as the Eurasian tree sparrow, house sparrow, and starling, show a moderate increase of about 15 percent.

“The species showing the strongest increase is the European goldfinch, whose population has grown by as much as 54 percent since 2000.”

Buskskvett=Whinchat, Gråspurv=House Sparrow, Gråtrost=Fieldfare, Grønnfink=European Greenfinch, Gulspurv=Yellowhammer, Heipiplerke=Meadow Pipit, Kaie=Eurasian Jackdaw, Kråke=Hooded Crow, Linerle=White Wagtail, Låvesvale=Barn swallow, Pilfink=Eurasian Tree sparrow, Ringdue=Wood Pigeon, Sanglerke=Skylark, Skjære=Eurasian Magpie, Stillits=European Goldfinch, Storspove=Eurasian Curlew, Stær=European Starling, Taksvale=House Martin, Tornirisk=Common Linnet, Tornsanger=Common Whitethroat, Tårnseiler=Common Swift, Vipe=Northern Lapwing.

Several causes behind the decline

It is important to remember that there are major differences among the bird species found in the agricultural landscape. They have different preferences and ways of life. Therefore, it is not possible to point to a single cause explaining why so many species are declining. On top of this, climate change may also play a role.

Pedersen notes that some of the 22 species are resident birds that are present in Norway year-round. Others are migratory birds that overwinter farther south in Europe or in Africa. It is difficult to say with certainty to what extent the causes of decline are found in Norway, or whether they are due to conditions along migration routes or in wintering areas.

“However, the fact that we also see declines among species that remain in Norway all year means that we must take a large share of responsibility for what is happening here,” Pedersen explains. At the same time, cooperation across national borders must be strengthened.

Changes in land use are the main explanation

According to the researcher, historical and ongoing changes in the content and use of the landscape are the primary explanation for the decline. When agricultural landscapes become more uniform—either through intensification, larger and more specialized production systems, or due to agricultural land abandonment causing overgroth—important habitats for many bird species disappear.

“Field margins, small woodlots, pastures, wetlands, and small habitat features provide food, shelter, and nesting sites. When these landscape elements disappear, the basis for bird life is weakened. In addition, some species nest directly on farmland and are therefore in direct conflict with food production. This applies, for example, to the northern lapwing, Eurasian curlew, and skylark,” Pedersen explains.

For these species, intensified management of production areas is particularly challenging, for example when the growing season is extended by increasing the number of hay cuts. Increased drainage also poses a challenge.

Measures can reverse the trend

The results from the 3Q programme provide an important knowledge base for management and agricultural policy.

To slow down and eventually reverse the negative trend, the researchers recommend, among other measures:

- Preserving and facilitating habitats to ensure access to food and shelter

- Adapting farming practices to birds’ life cycles

- Protecting field margins, small woodlots, and wetlands

- Managing grazing areas and hay meadows

- Reducing the use of pesticides

- Preventing overgrowth and afforestation with coniferous forest

Several existing environmental subsidy schemes that were originally established for other purposes may already have a positive effect on birdlife, and some schemes could potentially be adjusted to strengthen this effect.

A symptom of something bigger

“When bird populations decline, it is often a signal of more fundamental changes in nature,” says Pedersen. Birds occupy high positions in the food chain and respond quickly to changes in living conditions. They are therefore important indicators of environmental status and ecosystem health.

Fewer flowering plants, for example, lead to fewer pollinating insects—and thus fewer birds.

“Unfortunately, the negative trend does not appear to be reversing anytime soon. That is why it is urgent to implement measures that can help bird populations increase, or at least stabilize,” Pedersen concludes.

Contacts

Systematic monitoring through the 3Q programme

Trends in bird populations are documented through the 3Q programme, in which breeding birds have been monitored since 2000. Monitoring takes place on 130 fixed plots of one square kilometre each, spread across the entire country. On each plot, birds are recorded at nine fixed points, and surveys are conducted every three years.

The data provide a unique time series showing how populations of bird species in agricultural landscapes have developed over more than 20 years.

Contacts

Publications

Abstract

Fuglebestandene i det norske jordbrukslandskapet går tilbake. Nye tall fra 3Q-programmet viser en nedgang på rundt 25 prosent siden 2000. Utviklingen tyder på at endringer i arealbruk og driftsformer påvirker leveområdene til mange arter, og viser behovet for målrettede tiltak for et mer variert jordbrukslandskap.

_cropped.jpg?quality=60)

_(Eurasian_skylark)_Steinodden._Lista._Norway.jpg?quality=60)