European goldfinch – a splash of colour in the Norwegian cultural landscape

The European goldfinch is easy to recognize by its red face and bold yellow wing bars. Photo: Andreas Günther

There’s a lot of bad news about nature crisis and birds that are declining. But some birds are doing well in Norway – like the European goldfinch.

The European goldfinch is a small, colourful, and quite social finch. Despite its beautiful appearance, it is not among our best-known bird species. When seeing a goldfinch for the first time, it’s easy to think it has escaped from captivity. Birds this brightly coloured are often associated with southern latitudes.

The goldfinch can be recognized by its small, pointed beak, distinctly notched black tail, white rump, red face, and bold black-and-white head markings. The back is light brown and the underside is white. The wings are black with broad yellow wing bars.

In goldfinches, it’s not just the male that has colourful markings - both sexes look almost identical. Juveniles lack the red facial mask but are still relatively easy to identify by their characteristic wing patterns.

Specialist in weed seeds

The goldfinch can be found in many different habitats, but it avoids dense forest and completely treeless areas. It feeds mainly on seeds, usually taken directly from flowers or seed heads, but can also be seen eating seeds on the ground.

With its small, pointed beak, the goldfinch is specially adapted to feeding on seeds from composite plants such as groundsel, knapweed, thistles, and burdock species.

Despite its bright colours, goldfinches can be surprisingly hard to spot when quietly feeding on weed seeds along roadsides or field edges. When they take off, it’s often the yellow wing bars that give them away.

Often you hear the goldfinch before you see it. The Norwegian name stillits comes from the German Stieglitz, which refers to the bird’s distinctive call, “tikk tikkeli tikkelitt.” In other words, stillits is an onomatopoeic name.

The goldfinch is usually quite social, and outside the breeding season it is often seen in flocks of 5–40 individuals. It can also form larger mixed flocks with other finches, such as siskins, linnets, and greenfinches.

Distribution and population growth

The European goldfinch is naturally found throughout most of Europe, North Africa, and western parts of Central Asia. It has also been introduced to countries such as Australia, New Zealand, the USA, Uruguay, and Argentina.

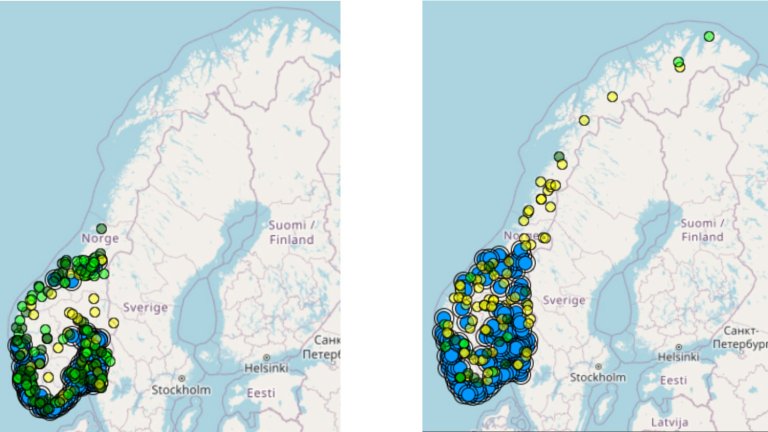

In Norway, it is most common in the lowlands of Eastern Norway, especially around the Oslofjord, but also further up the Gudbrandsdalen valley, as well as scattered along the coast from Østfold to Rogaland.

The goldfinch has always been relatively rare in Norway, but in recent decades it appears to have become more common, while also expanding its range both northwards and inland. The species has, for example, established itself in Trøndelag county, where the first confirmed breeding record was documented in 2017.

The goldfinch has also seen positive population trends in our neighbouring countries. In Sweden, it is one of the breeding birds that has increased the most in number over the past ten years. This may be related to the fact that the species has increasingly begun to visit bird feeders in winter.

Monitoring prevents change blindness and poor memory

“It’s important to monitor changes over time,” explains NIBIO researcher Wenche Dramstad.

“We humans generally suffer from change blindness and poor memory. We quickly assume that ‘it has always been this way.’ That’s why monitoring data can help us notice changes in nature. Things may not change dramatically from year to year, but rather gradually and subtly.

There’s a lot of natural fluctuation - variation between years is the rule rather than the exception. For many species, for example, a cold and late spring can have a major impact. The same goes for an extra cold or snowy winter. It’s only when we look at long-term trends that we can really find out whether there is a development in one direction or the other.

Detecting such changes is a key driver in the monitoring work NIBIO does, for example in the 3Q program. It was farsighted of ministries and directorates back in 1998 to initiate this monitoring,” Dramstad explains.

At that time, significant changes in the agricultural landscape had been observed, and reports were increasingly pointing out the consequences. Some of these changes posed challenges especially for species that depend on agricultural landscapes, such as the northern lapwing and Eurasian skylark.

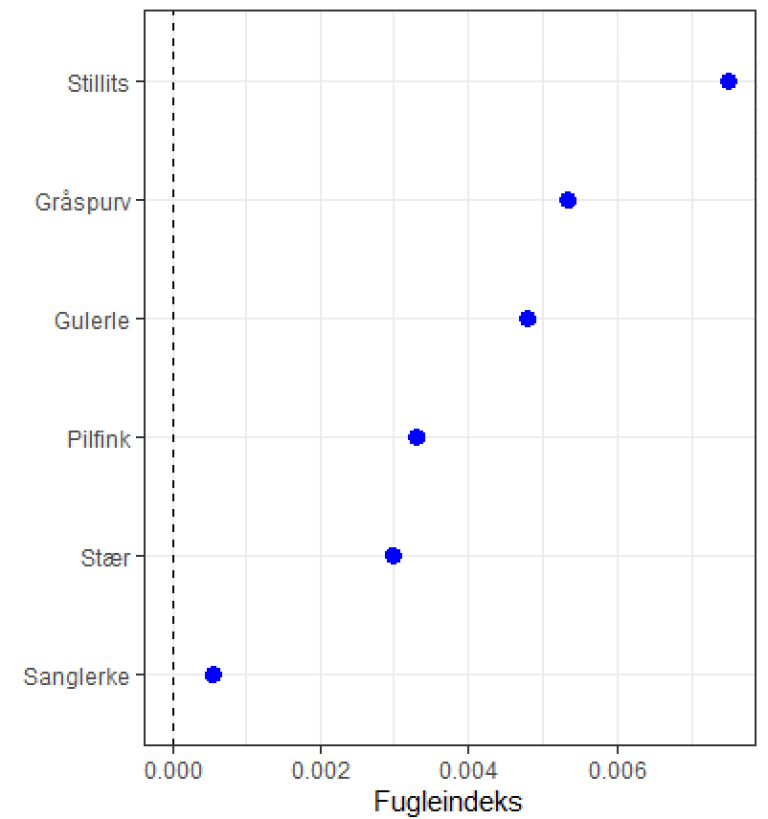

Fortunately, there are also species in the agricultural landscape that seem to be doing well over time. Some appear to be increasing in number while also expanding their range. The beautiful European goldfinch is one of them.

Contacts

Listen to the song of European goldfinch

ABOUT THE 3Q PROGRAM

The monitoring program “Monitoring and Performance Control in Agricultural Cultural Landscapes”, commonly known as 3Q, has been run by NIBIO since 1998. Its goals include monitoring land use and land-use changes, as well as tracking how these changes affect biodiversity - initially focusing on birds and vascular plants, and later also butterflies and bumblebees.

By comparing aerial photographs from different years, changes in the landscape become clear. Researchers can see how the number and size of fields change, how new road projects appear, how farmyards and farm roads expand, and how field margins and farm ponds disappear, or new ones are created.

The 130 monitoring plots where birds are counted are spread across agricultural landscapes throughout Norway. Each plot covers an area of 1 x 1 km. On each plot, nine points are designated, and within a circle with a 50 m radius around each point, researchers record both the number of breeding bird pairs and various vegetation details. This allows them to understand the habitat requirements of different bird species and which landscape configurations support the highest number of individuals or species.

Each monitoring plot is surveyed every third year, and over time the researchers build a time series that shows population trends for the various bird species.

Contacts

_cropped.jpg?quality=60)

_(Eurasian_skylark)_Steinodden._Lista._Norway.jpg?quality=60)