Higher water levels could turn cultivated peatland in the North into a CO2 sink

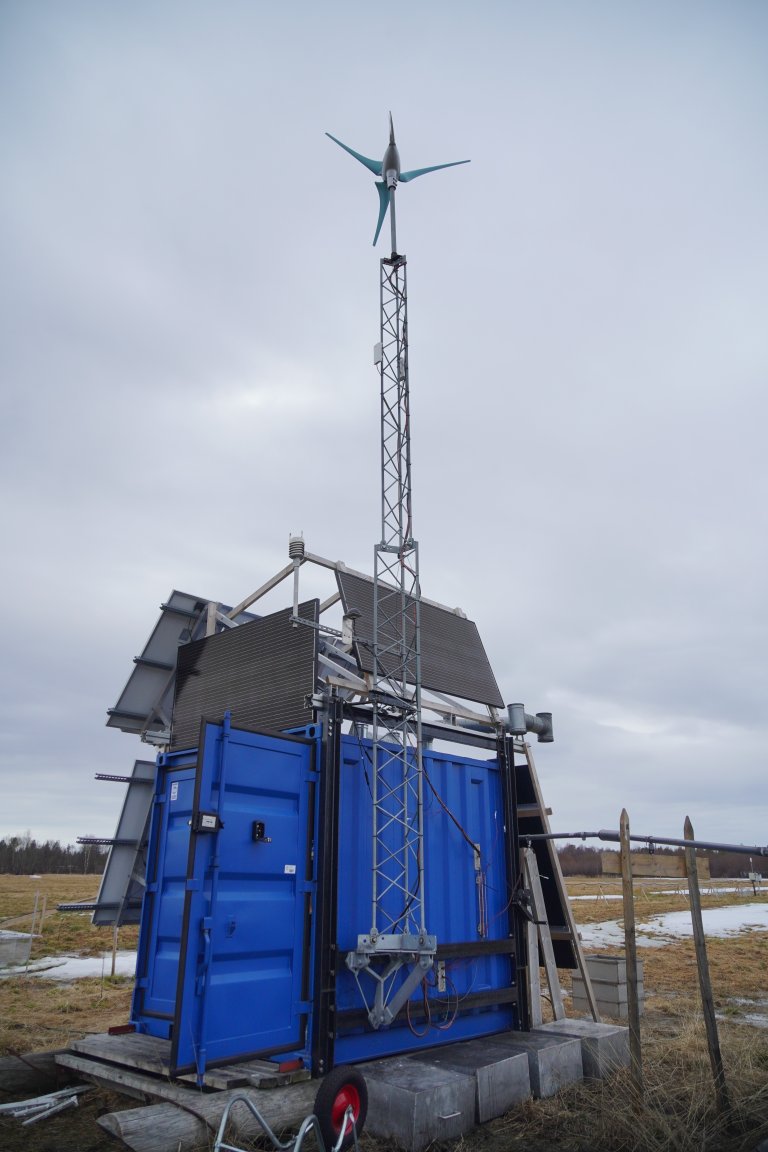

In 2022 and 2023, NIBIO-researcher Junbin Zhao and his colleagues carried out an extensive field experiment at NIBIO’s station at Svanhovd in the Pasvik Valley in Finnmark, Northern Norway. Here, automated chambers measured emissions of CO₂, methane and nitrous oxide from the cultivated and drained peatland several times a day throughout the growing season. Photo: Junbin Zhao

A two year field experiment carried out in the world’s northernmost cultivated peatland, located in Pasvik in Finnmark, shows that greenhouse gas emissions can be greatly reduced by raising and maintaining the water table at 25–50 centimetres below the soil surface.

In its natural state, peatland is one of the largest carbon stores in nature. This is because the soil is so waterlogged and low in oxygen that dead plant material breaks down very slowly. The plants do not fully decompose but instead accumulate over thousands of years, forming thick layers of peat.

When a peatland is drained for agricultural use, the water level drops and oxygen enters the peat layer. Microorganisms can then break down the old plant material much faster, releasing carbon that has been stored for many years as the greenhouse gas carbon dioxide (CO₂).

Well‑studied in the South, but not in the North

Since the 1600s, large peatland areas in Europe and the Nordic region have been drained, and many studies have investigated how drainage and changing water levels influence greenhouse gas emissions.

However, there is little knowledge from the northernmost drained peatlands, where the climate is characterised by low temperatures, long, light summer nights, and short growing seasons.

“From studies in warmer regions, we know that raising the groundwater level in drained and cultivated peatland often reduces CO₂ emissions, because the peat decomposes more slowly,” explains NIBIO researcher Junbin Zhao.

“At the same time, wetter and low‑oxygen conditions can increase methane, since the microbes that produce methane thrive when there is almost no oxygen in the soil.”

Under certain conditions, nitrous oxide emissions may also rise. This happens when the soil is moist but not fully waterlogged, so that nitrogen breakdown stops halfway and produces nitrous oxide instead of harmless nitrogen gas.

“Because each greenhouse gas reacts differently to changes in water level, one gas can go down while another goes up. That’s why it’s important to look at the overall gas balance,” says Zhao.

“We need to measure CO₂, methane, and nitrous oxide at the same time and throughout the whole season to understand the real net effect in the northernmost agricultural areas.”

Two‑year field trial in the Pasvik Valley, Finnmark

In 2022 and 2023, Zhao and colleagues conducted an extensive field trial at NIBIO’s station at Svanhovd in the Pasvik Valley in Northern Norway. Automatic chambers measured CO₂, methane, and nitrous oxide emissions several times a day throughout the growing season.

“The experiment included five plots that together reflected typical management conditions found in a drained agricultural field - with different groundwater levels, different amounts of fertiliser, and different numbers of harvests per season,” Zhao explains.

The researchers wanted to answer three questions:

- Can raising the groundwater level make a cultivated Arctic peatland close to climate‑neutral?

- Does the water level affect soil CO₂ emissions more than it affects plant CO₂ uptake?

- How do fertilisation and harvesting influence the total climate balance?

High water levels reduced emissions

The results showed that when the peatland in Pasvik was well drained, it emitted large amounts of CO₂ — about the same as other cultivated peatlands further south.

However, when the groundwater was raised to 25–50 cm below the surface, emissions dropped sharply.

“At these higher water levels, methane and nitrous oxide emissions were also low, giving a much better overall gas balance. Under such conditions, the field even absorbed slightly more CO₂ than it released,” says Zhao.

High groundwater in cultivated Arctic peatland may therefore be an effective climate measure.

“Our findings are especially interesting because emissions were measured continuously around the clock. This meant we captured short spikes of unusually high emissions and natural daily fluctuations, details often missed when measurements are taken only occasionally.”

.jpg)

Works best in cold climates

When the groundwater is high, the soil becomes wetter and oxygen levels in the root zone fall. Under these conditions, plants are less active and take up less CO₂.

Even so, the total CO₂ emissions decrease in the field.

“This is because wet conditions mean that the field needs less light before it starts to absorb more CO₂ than it releases. When this threshold is reached earlier in the day, you get more hours with net carbon uptake,” Zhao explains.

“Our calculations show that this effect is especially strong in the north, due to the long, light summer nights. These provide many extra hours where the system remains on the positive side, which can increase total CO₂ uptake significantly.”

Temperature, however, proved to be a key factor. The researchers found that when soil temperatures rose above about 12°C, microbial activity increased.

“At higher temperatures, microorganisms break down organic material faster, and both CO₂ and methane emissions rise,” says Zhao.

“This means that the effect of high water levels is greatest in cool climates — and that future warming could reduce the benefit. In practice, this means water levels must be considered together with temperature and local conditions.”

Fertilisation and harvesting: balancing production and carbon

Fertilisation and harvesting also affected the climate balance. When the researchers applied more fertiliser, the grass grew better.

“More fertiliser produced more biomass but did not lead to noticeable changes in CO₂ or methane emissions in our experiment,” says Zhao.

Harvesting, however, had a clear effect. When the grass was cut and removed, carbon was removed from the system because plants store carbon as they grow.

“If harvesting is very frequent, more carbon can be taken out than is built up again over time. The peat layer may gradually lose carbon even when water levels are kept high,” Zhao explains.

He says it is therefore important to consider water level, fertilisation, and harvesting strategy together. Measures that reduce emissions in the short term may reduce carbon storage in the long term, which can weaken soil health.

“One solution could be paludiculture, i.e. growing plant species that tolerate wet conditions so that biomass can be produced without keeping the soil dry.”

Local variations can alter the climate balance

The researchers found large differences in emissions within the same field. Some areas absorbed CO₂, while others released large amounts.

“Such local variation can greatly influence national climate accounting and how measures are designed, because one standard emission factor may not reflect reality everywhere,” Zhao says.

“The results from our study show a clear need for more detailed measurements and more precise water‑level management in practice, especially where soils and farming conditions vary significantly between locations.”

Contacts

Contacts

Publications

Authors

Junbin Zhao Cornelya Klutsch Hanna Marika Silvennoinen Carla Stadler David Kniha Runar Kjær Svein Wara Mikhail MastepanovAbstract

Drained cultivated peatlands are recognized as substantial global carbon emission sources, prompting the exploration of water level elevation as a mitigation strategy. However, the efficacy of raised water table level (WTL) in Arctic/subarctic regions, characterized by continuous summer daylight, low temperatures and short growing seasons, remains poorly understood. This study presents a two‐year field experiment conducted at a northernmost cultivated peatland site in Norway. We used sub‐daily CO 2 , CH 4 , and N 2 O fluxes measured by automatic chambers to assess the impact of WTL, fertilization, and biomass harvesting on greenhouse gas (GHG) budgets and carbon balance. Well‐drained plots acted as GHG sources as substantial as those in temperate regions. Maintaining a WTL between −0.5 and −0.25 m effectively reduces CO 2 emissions, without significant CH 4 and N 2 O emissions, and can even result in a net GHG sink. Elevated temperatures, however, were found to increase CO 2 emissions, potentially attenuating the benefits of water level elevation. Notably, high WTL resulted in a greater suppression of maximum photosynthetic CO 2 uptake compared to respiration, and, yet caused lower net CO 2 emissions due to a low light compensation point that lengthens the net CO 2 uptake periods. Furthermore, the long summer photoperiod in the Arctic also enhanced net CO 2 uptake and, thus, the efficacy of CO 2 mitigation. Fertilization primarily enhanced biomass production without substantially affecting CO 2 or CH 4 emissions. Conversely, biomass harvesting led to a significant carbon depletion, even at a high WTL, indicating a risk of land degradation. These results suggest that while elevated WTL can effectively mitigate GHG emissions from cultivated peatlands, careful management of WTL, fertilization, and harvesting is crucial to balance GHG reduction with sustained agricultural productivity and long‐term carbon storage. The observed compatibility of GHG reduction and sustained grass productivity highlights the potential for future paludiculture implementation in the Arctic.