How will deer be affected by climate change?

Marshlands will become increasingly important for moose in the warmer climate of the future. Photo: Ingrid Bjørndal Foss

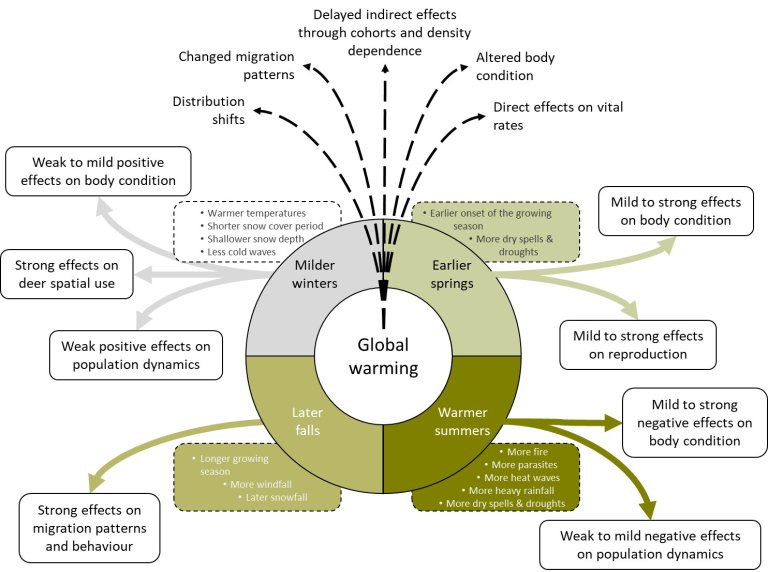

Although milder winters can be beneficial for many deer populations in the northern hemisphere, warmer summers with changing precipitation will likely cause more stress for the animals and push the populations further north.

NIBIO researcher Hilde K. Wam is part of a European research group that has compiled 20 years of research on how climate change is likely to affect deer species living in Europe, Asia, and North America.

The research article is based on a review of 218 scientific studies. It provides an overview of global trends regarding how climate change is likely to impact the physiology, behaviour, and population dynamics of deer species that live wholly or partially in boreal and temperate forests in the Northern Hemisphere.

Moose, roe deer, and red deer are well-known species in Norway, but the researchers have also looked at studies of fallow deer, forest reindeer, sika deer, white-tailed deer, and mule deer (black-tailed deer).

Climate change affects deer on many levels

Temperature, precipitation, snow conditions, and extreme weather—all these factors directly affect wildlife. For wildlife management, it is crucial to understand how such weather factors influence the animals' physiology, population sizes, and distribution.

“It starts with each individual animal,” Wam explains.

“When more animals are affected, it has an impact on the local populations, and eventually on the species over larger areas. When this continues for several generations, changes manifest in the animals' genetics, and ultimately, they become part of the process of evolution.”

The most important finding from the research is that changes in summer weather will likely have a greater impact on the future of these deer species than changes in winter weather. There will also be significant differences depending on where the animals are located along the geographical gradient from south to north.

“Rising global temperatures generally mean milder winters in the northern hemisphere, which can be locally beneficial for many deer species: they need less energy to stay warm, and it can be easier to find food as long as the snow isn’t replaced by ice.

“On the other hand, warmer summers and changing precipitation will likely exceed the tolerance limits of some populations, particularly regarding heat stress and parasites. Another clear finding is that deer are significantly more exposed to parasites in warmer and wetter weather. In the short term, this stress will lead to poorer physical condition in the animals. In the long term, it may cause the southernmost populations to die out, while the species shifts northward, thereby changing its distributional range.”

The researcher notes that this is already happening with the moose, the largest of the deer species and one of the species best adapted to cold climates. Moose are highly sensitive to heat stress, and the southernmost moose populations will therefore be more affected by climate change than those living further north. This difference between southern and northern populations has already been demonstrated in data from Sweden.

Climate change may cause behavioural changes in deer

If local conditions allow, some deer may be able to mitigate the negative effects of a warmer climate.

“They can, for instance, spend more time in other parts of the landscape than they normally would, or adjust their activity patterns throughout the day. Moose, for example, may spend more time in marshlands or older forests to cool down. It’s therefore important that the animals' habitats provide everything they need to adapt,” emphasizes Wam.

Warmer springs and autumns mean that the ground is snow-covered for a shorter part of the year, and the snow is also not as deep. This affects the animals’ seasonal migrations. For example, they are likely to begin migrating earlier in the spring, face floods and hazards at different times than they are adapted to, and because the growing season is longer, they may delay their migration back in the fall. Altogether, this may lead some populations of migratory species to eventually stop migrating between seasonal feeding grounds altogether.

“It’s hard to say exactly what the future climate will look like and how it will affect deer species. Our article doesn’t provide definitive answers, but so far, this is the largest compilation of knowledge we have on deer species relevant to Norway,” concludes Wam.

Contacts

Contacts

_cropped.jpg?quality=60)