Fire-scarred trees record 700 years of natural and cultural fire history in a northern forest

Boreal fire. Photo: Ken Olaf Storaunet.

Until the modern era, the human mark on the northernmost forests of North America, Europe, and Asia was light. Human populations in these challenging environments were too small to make a big impact through agriculture or timber harvests. But increasing evidence indicates people influenced the northern forests indirectly, by igniting or suppressing fires.

Distinguishing human from climatic influence on historical fire patterns is critical to forest management planning, which is guided by historical patterns of fire frequency, size, and intensity.

A boreal forest nature reserve in southern Norway offered a unique opportunity to reconstruct past events, as scientists from the Norwegian Institute of Bioeconomy Research (NIBIO) demonstrated in a report published online ahead of print in the Ecological Society of America’s journal Ecological Monographs. The trees told a story of a surge in human-instigated fires during the 17th and 18th centuries, followed by fire suppression after AD 1800, as economic motivations changed.

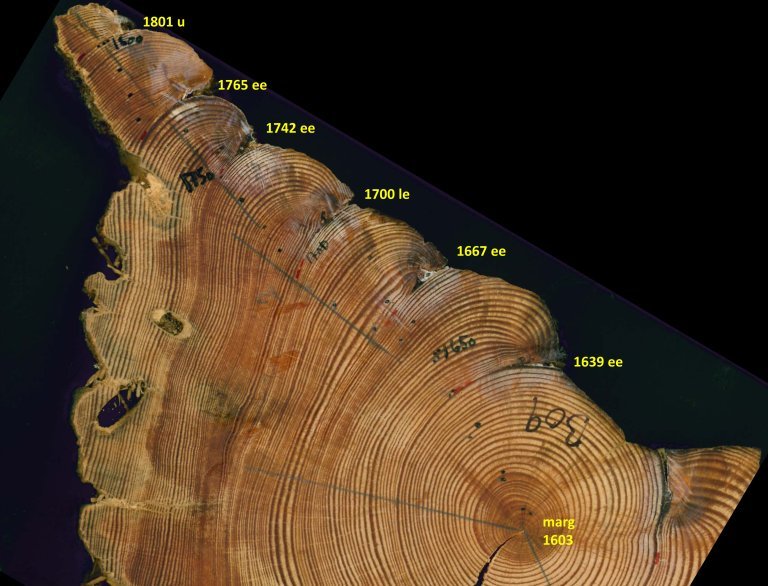

Unlike the boreal forests of North America, which more frequently experience fires hot enough to kill most trees, the forests of Norway, Sweden, and Finland characteristically burn at low to medium intensity. Fires burn through the understory, leaving mature trees scarred, but living. The burn scars, combined with tree ring data, and historical documents, present a record of wildfire behavior in the second millennium.

Together with former PhD-student Ylva-li Blanck of the Norwegian University of Life Science, researchers Jørund Rolstad and Ken Olaf Storaunet collected and analyzed 459 wood samples from old, fire-damaged pine tree stumps, snags, downed logs and living trees in 74 square kilometers (28 square miles) study area in Trillemarka-Rollagsfjell nature reserve.

At 60 degrees North, Trillemarka-Rollagsfjell shares a latitude close to Anchorage, Alaska and Whitehorse, the capital of Canada’s Yukon province. The pine and spruce dominated forest ecosystem has many traits in common with the forested ecosystems of interior Alaska and Canada.

The collected samples were cross-dated by dendrochronology, a method used to date wooden samples by comparing tree rings with a known time-sequence from many other collected and dated tree ring series. In this way, scientists can determine the date and location of forest fires with great accuracy. Based on where in the tree ring the damage occurred, the forest researchers can also say at what time of the year it burned.

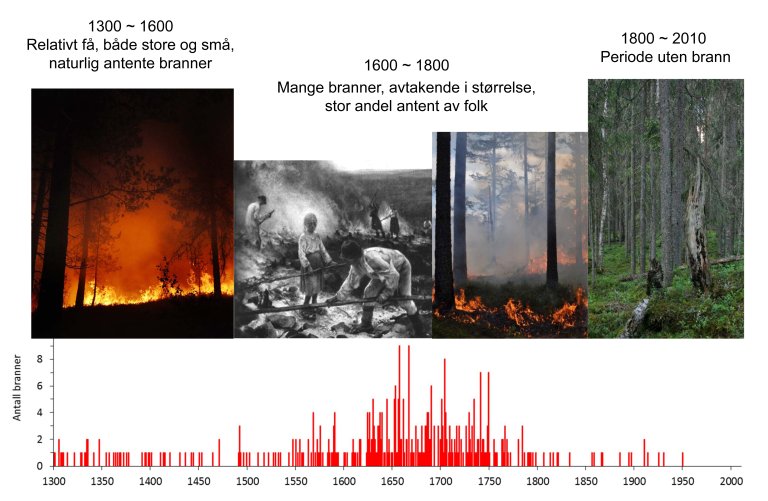

From this record, the authors estimated fire location, frequency, size, and seasonality over the last 700 years, comparing the fire history to historical records from the National Archives of Norway, including juridical documents, diplomas, and old maps of the area and old agricultural textbooks and reports. They dated 254 individual fires from AD 1257-2009. The oldest living tree they sampled dated to AD 1515 and the oldest stump to AD 1070.

From AD 1300 to 1600, wildfires ignited during late summer, with about 5-10 ignitions per quarter century, generally occurring during warm, dry summers.

In the next two centuries, fire frequency rose dramatically, particularly in the mid-17th century. Early summer fires grew in prevalence. Books and other documents from this time period record a rising use of slash-and-burn cultivation and rangeland burning, explained author Ken Olaf Storaunet. The population was recovering from the devastation of the Black Death and several subsequent epidemics. People returned to abandoned lands and began using fire to improve land for grazing animals and to cultivate crops. The average length of time between recurrences of fire in the same location fell by half, from 73 to 37 years.

Increasing demand for timber in Europe raised the value of forests and discouraged slash-and-burn cultivation practices. The fires legislation banning the use of fire in Norway came in 1683. After AD 1800, fire frequency and size dropped precipitously, with only 19 fires occurring in the study area during the last 200 years.

Ecologically, the period from 1625 and onwards to today is probably unique, and something that perhaps has not happened in thousands of years, Storaunet said.

Studies in Alaska and Canada have projected that hotter, drier summers may increase annual wildfire burn areas by two to three times by the end of the century. In Norway, the North Atlantic Ocean may temper hotter summers with more precipitation.

Forest fires can be catastrophic and damaging for both home owners and the forest industry. In Canada each year, on average, 8,600 fires burn 25,000 square kilometers (10,000 square miles) of forest.

But forest fires play an important part in the ecology of northern forests. Natural forests are not a continuous expanse of old trees. Forest fires create a mosaic of burnt and unburnt areas, shaping the species composition and the age distribution of the forest. Fires open up the tree canopy, letting light in, releasing nutrients to the understory, and aiding regrowth. Charcoal changes soil structure, and charred tree trunks become habitats of great importance for the biological diversity of the forest—both above and below ground. Many rare species, especially fungi and insects, depend on the variation forest fires create.

Many of today’s forest reserves have perhaps never been as unnatural as they are today, Storaunet pointed out.

The historical studies in Trillemarka-Rollagsfjell nature reserve show that fire has been a natural, and very dynamic, part of the forest ecosystem throughout history. And this ecosystem is affected by climate, vegetation and not least the way humans use forest, Storaunet said.

See animation of the mapped forest fires in Trillemarka through 700 years:

Contacts

Contacts