Drones and satellites can measure methane emissions from ruminants

Alouette van Hove from the University of Oslo, during trials with drones at ILRI Kapiti Research Station in Kenya. Photo: Vibeke Lind / NIBIO

A new study combines drone data, satellite observations, and ground-based flux measurements to examine methane emissions from ruminants in Kenya. The research represents a pioneering effort to quantify methane (CH₄) emissions from livestock using drones in sub-Saharan Africa. It is also among the first field studies to measure methane emissions from camels, a largely understudied source.

Methane emissions from livestock account for roughly one-third of global anthropogenic methane emissions, yet they remain poorly mapped in many regions—particularly in Africa.

Using drones equipped with methane sensors, researchers flew over herds of cattle, goats, sheep, and camels before and after grazing to capture methane concentration data. Wind measurements were provided by a ground-based flux tower.

The study was conducted at ILRI Kapiti Research Station in Kenya, in collaboration between the University of Oslo, ILRI, NIBIO, and the University of Milan. Initial test flights were carried out at NIBIO’s research station at Tjøtta in northern Norway. The results may contribute to more accurate estimates of livestock methane emissions, supporting their inclusion in climate models and national greenhouse gas inventories.

A flexible method for measuring greenhouse gas emissions in remote areas

“This study demonstrates that drones can effectively monitor emissions in remote or challenging environments, where traditional chamber methods are unavailable or impractical—particularly for large animals such as camels,” says Alouette van Hove, from the University of Oslo and first author of the study.

Her research focuses on developing new methods for measuring and calculating greenhouse gas emissions, such as methane and CO₂, including emissions from agriculture, using sensor-equipped unmanned aerial vehicles (drones).

“It’s a flexible approach that allows researchers to travel to the animals’ location and collect measurements over several days and at different times, without disturbing the animals,” she adds.

The article, “Inferring methane emissions from African livestock by fusing drone, tower and satellite data”, is part of the CircAgric-GHG research project. The project aims to uncover mechanisms through which farming systems can enhance circularity, reduce greenhouse gas emissions, and deliver ecosystem services at multiple scales.

A reliable method

The researchers applied a Bayesian inference method that integrates drone-based methane measurements and flux-tower wind data with an atmospheric dispersion model. This probabilistic approach accounts for uncertainty in the data and incorporates prior knowledge to produce more reliable emission estimates.

Three approaches were compared:

- Bayesian inference (probabilistic, data-driven)

- Mass balance method (based on methane inflow and outflow in a defined area)

- IPCC Tier 2 estimates (standardized values based on diet, activity, and animal type)

The researchers assessed how closely the results from the different methods aligned with IPCC estimates.

“We found that the Bayesian inference method consistently produced results in line with IPCC Tier 2 estimates—even for low-emission animals such as goats and sheep—indicating that the method is both reliable and robust under the conditions of the study,” says van Hove.

By contrast, the mass balance method often overestimated emissions from low-emission animals, suggesting limitations when applied to weaker sources.

Vibeke Lind, Research Professor at NIBIO and project leader of CircAgric-GHG, was responsible for calculating the IPCC Tier 2 methane emission estimates for the livestock monitored by the drones.

“The Tier 2 values incorporate detailed herd- or animal-specific data. In this study, the data accounted for local conditions in Kenya, including livestock breeds and feed quality. We used the method to estimate emissions from individual animals based on weight, age, feed intake, and feed quality,” says Lind.

Integrating satellite data

Another innovation in the study is the integration of hyperspectral satellite data. Researchers from the University of Milan used imagery from the Italian Space Agency’s PRISMA satellite, acquired over the Kapiti farm during the same period as the drone campaign.

The aim was to assess whether hyperspectral satellite sensors could detect landscape features associated with herd locations and potential methane emissions.

Satellite imagery is typically used to identify large emission sources, such as industrial gas leaks. The researchers were therefore keen to explore whether satellites could detect spatial anomalies directly or indirectly linked to livestock emissions.

The results showed that satellite images detected anomalies precisely at herd locations. However, further research is needed to determine whether these anomalies were caused by elevated methane concentrations or by other factors, such as changes in vegetation or soil moisture.

“Although this was an exploratory analysis, the results suggest potential for multi-scale assessment of point emission sources at the landscape level by combining drones with next-generation spaceborne hyperspectral sensors,” says Associate Professor Francesco Pietro Fava of the University of Milan.

Identifying emission sources and estimating volumes

The method presented in the study can be likened to zooming in on a map—from a distant overview to the detail of a single pixel.

“Satellites help identify emission sources, while drones provide information on emission concentrations and daily variations, such as before and after feeding,” says Lind.

At an even finer scale, emissions from individual animals can be measured using methods such as respiration chambers, the SF₆ tracer gas technique, or face masks.

“Although drones show great promise, they currently require certified operators and data specialists, which limits their accessibility for most farmers. Nevertheless, the technology has strong potential for identifying emission sources and estimating emission volumes,” Lind concludes.

What’s next?

Accurate, localized measurements are essential for developing effective mitigation strategies. This research could inform discussions on feed subsidies, grazing practices, and emission reduction policies—particularly in regions where data is scarce.

The study also lays the groundwork for expanding methane mapping to other sources, including wetlands, landfills, and thawing permafrost. Adapting the framework to handle multiple diffuse sources and overlapping emission plumes will be necessary to improve its applicability in complex landscapes.

As Alouette van Hove notes:

“It’s exciting to work on something that can actually make a difference. Measuring methane from cows is not just a technical challenge — it’s a way to support better decisions for climate and agriculture.”

She is now working on optimizing drone flight paths using machine learning, enabling drones to autonomously detect and estimate methane sources in environments where their locations are unknown —“like smelling where the cows are,” as van Hove puts it. This could further improve efficiency and accuracy in future monitoring campaigns.

Contacts

What the Research Reveals

Methane emissions increase after feeding, confirming known patterns of enteric fermentation.

Bayesian inference estimates of weak sources were more accurate than those from the traditional mass balance method. The method also performed better under variable wind conditions.

Drone-based methods are flexible, allowing measurements across species, landscapes, and timeframes.

Satellite data may help locate emission hotspots, guiding future drone missions.

Contacts

Publications

Authors

Alouette van Hove Kristoffer Aalstad Vibeke Lind Claudia Arndt Vincent Odongo Rodolfo Ceriani Francesco Fava John Hulth Norbert PirkAbstract

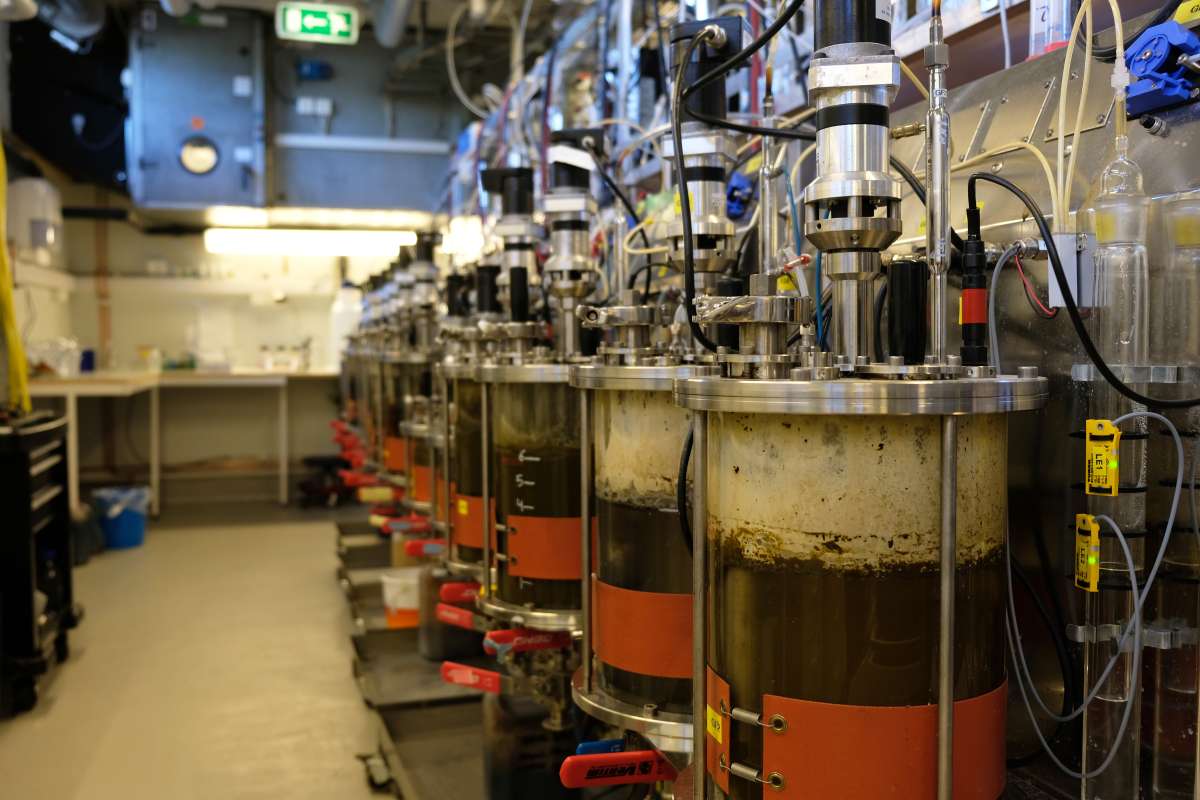

Considerable uncertainties and unknowns remain in the regional mapping of methane sources, especially in the extensive agricultural areas of Africa. To address this issue, we developed an observing system that estimates methane emission rates by assimilating drone and flux tower observations into an atmospheric dispersion model. We used our novel Bayesian inference approach to estimate emissions from various ruminant livestock species in Kenya, including diverse herds of cattle, goats, and sheep, as well as camels, for which methane emission estimates are particularly sparse. Our Bayesian estimates aligned with Tier 2 emission values of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. In addition, we observed the hypothesized increase in methane emissions after feeding. Our findings suggest that the Bayesian inference method is more robust under non-stationary wind conditions compared to a conventional mass balance approach using drone observations. Furthermore, the Bayesian inference method performed better in quantifying emissions from weaker sources, estimating methane emission rates as low as 100 g h−1. We found a ± 50 % uncertainty in emission rate estimates for these weaker sources, such as sheep and goat herds, which reduced to ± 12 % for stronger sources, like cattle herds emitting 1000–1500 g h−1. Finally, we showed that radiance anomalies identified in hyperspectral satellite data can inform the planning of flight paths for targeted drone missions in areas where source locations are unknown, as these anomalies may serve as indicators of potential methane sources. These promising results demonstrate the efficacy of the Bayesian inference method for source term estimation. Future applications of drone-based Bayesian inference could extend to estimating methane emissions in Africa and other regions from various sources with complex spatiotemporal emission patterns, such as wetlands, landfills, and wastewater disposal sites. The Bayesian observing system could thereby contribute to the improvement of emission inventories and verification of other emission estimation methods.