Fungicide resistance – a threat to the health of humans, animals, and plants

NIBIO researcher Andrea Ficke leads the work to investigate the correlation between resistance in plant pathogenic fungi and resistance in Aspergillus fumigatus. Here she is together with senior engineer Jafar Razzaghian (left) and a Brazilian internship student, Mateus Morais (right). Photo: Silje Kvist Simonsen

Fungicides are important in the fight against harmful fungi, but researchers are concerned about the development and spread of fungicide resistant fungi. NIBIO and the Norwegian Veterinary Institute are collaborating to increase the knowledge about fungicide resistance in Norway.

Fungi can cause disease in both humans, animals, and plants. Every year, 1.5 million people die from fungal infections, and fungal attacks in food crops threaten food production. To protect ourselves, we have developed chemical agents - in the form of medicines or pesticides - that kill harmful fungi. The most effective remedy against fungal infections is a group of substances collectively known as azoles.

"It is vital that the azoles we use against pathogenic fungi have a good effect," says Ida Skaar, senior researcher at the Norwegian Veterinary Institute.

Azoles are indeed frequently used – as medicine for humans and animals, to prevent fungal diseases in food crops and on golf courses, to preserve wood, to prevent mould in flower bulbs and silage, and to preserve ornamental plants. The list is long. This frequent use causes researchers to worry because the harmful fungus develops resistance.

A little-explored topic

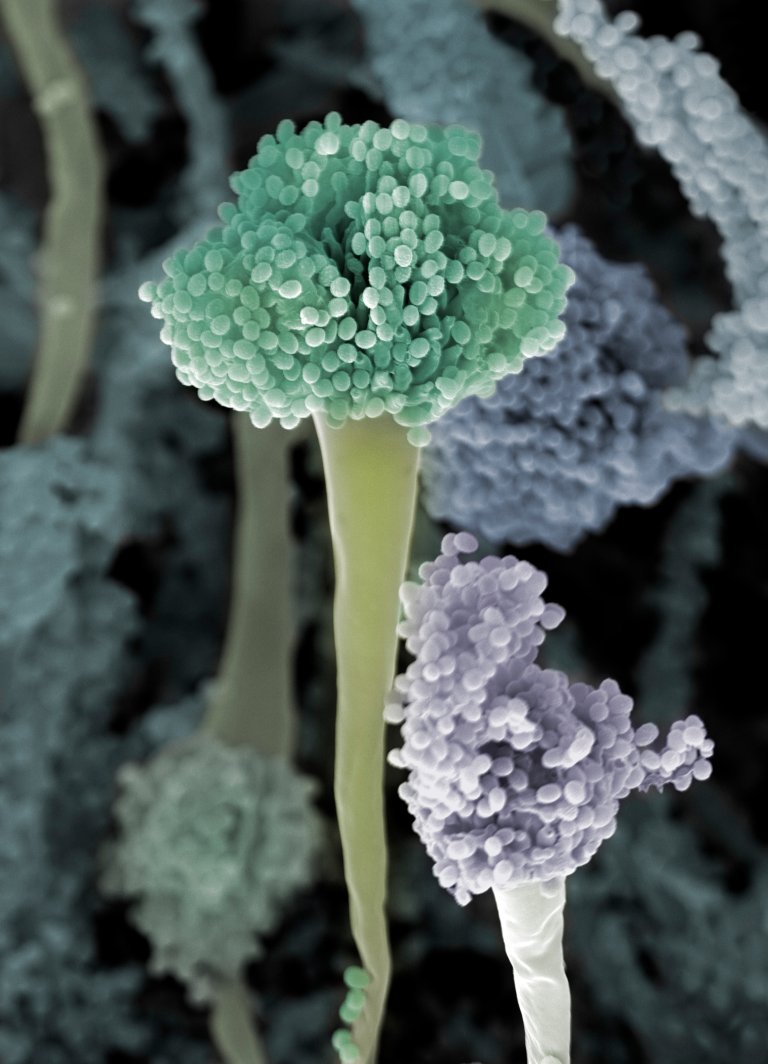

Antibiotic resistance is a well-known issue that raises concern among many. In comparison, fungicide resistance is a little-explored, but very relevant, topic. The World Health Organization (WHO) has, among other organisms, singled out the fungus Aspergillus fumigatus as a fungus that can pose a health threat in the future. A. fumigatus is a common fungus found everywhere, and it poses little threat to healthy people. For people with a compromised immune system, it can cause infections that need to be treated. In such cases it is vital that the medicine, which is usually based on azoles, is effective.

"A. fumigatus that is resistant to azoles is an increasing global problem," Skaar says.

"We do not know how the situation in Norway is, but with the wetter and warmer climate that we can probably expect in the future, the problem will become greater.

"Knowledge about the situation in Norway is absolutely necessary. We must be proactive and have the necessary knowledge before the problem becomes too serious. We must, among other things, know how much resistance we have, in what way the fungus develops resistance, and in which environments resistance is likely to arise (so-called hotspots).

One Health – everything is connected

Skaar leads the project NavAzole which aims to map and understand the development of azole resistance in Norway. This knowledge is needed to make wise decisions to keep the resistance level as low as possible. This requires cooperation between different sectors.

"Azole resistance concerns several sectors. We must therefore keep the One Health perspective in mind when working with it. This means that we must acknowledge the important connection between human health, animal health, and the surrounding environment. We need to consider all the application areas of azoles, and investigate hotspots for resistance development, and how resistance is spread further," the senior researcher elaborates.

Looking for resistance in soil dwelling fungi

A potential hotspot for resistance development is the use of azole-based pesticides in agriculture. In the project, NIBIO will work with this issue.

Andrea Ficke is a researcher from NIBIO, working with fungal diseases in cereals. She explains how a cereal field can be a hotspot for resistance development:

"A. fumigatus is a soil dwelling fungus that also exists in the field. In conventional agriculture, the crops are sprayed against various fungal diseases, and many of the fungicides are based on azoles. Some of the fungicides will end up in the soil and can affect A. fumigatus. In the same way that a high use of antibiotics can lead to bacteria developing resistance, regular exposure to azoles can lead to resistance in A. fumigatus. "

In the project, the researchers therefore want to investigate whether they find resistant A. fumigatus in cereal fields that are sprayed with azole-based fungicides, and whether there is a correlation between resistance development in plant pathogenic fungi and resistance development in A. fumigatus.

"We are going to study two fungi that cause the leaf blotch diseases septoria leaf blotch (Zymoseptoria tritici) and septoria nodorum blotch (Parastagonospora nodorum). These diseases can lead to a considerable loss of crops," Ficke explains.

Ficke has been working on leaf blotch diseases in cereals for 10-12 years. During these years, she has not observed a worrying increase in resistance to fungicides. So far, Skaar's research group has also not found resistant A. fumigatus in fields. However, this does not mean that we can rest on our laurels, quite the contrary.

Preventive work is important

"In Norway, we are very fortunate not to have major problems with fungicide resistance in crops," Ficke says.

Although Skaar has found more resistant A. fumigatus in various Norwegian environments than expected, she also believes that the problem is relatively small in Norway. "But you don't have to go further than to Denmark before the situation is more serious, " she adds.

Both researchers emphasize the importance of focusing on this issue in Norway.

"The preventive efforts we put in are crucial. We must understand the extent of the problem in Norway, and we must implement measures that can reduce the development of resistance. The use of integrated pest management plays an important role in this, by reducing unnecessary use of fungicides. In addition, one should consider in which situations it is necessary to use fungicides. "

"Norway excels at avoiding unnecessary use of antibiotics, and we should focus equally on avoiding unnecessary use of fungicides. When resistance becomes properly established, it is very difficult to eradicate. Therefore, we must be proactive," the researchers conclude.

How do fungi develop resistance?

In all fungal populations, there exists a certain genetic variation. This variation can make some "individuals" more tolerant to the exposure to fungicides than others. When the population is exposed to fungicides, these "individuals" will survive, and can reproduce. The resistance to fungicides is genetic, and thus hereditary. Random mutations can also occur in the DNA of the fungus, making it resistant. In this way, the use of the same type of fungicide over a long time will select for fungi that are increasingly resistant. The faster the fungi reproduce the faster resistance can occur.

Different fungicides have different strategies to kill or inhibit fungi. An "individual" that has developed resistance to one type of fungicide is not necessarily resistant to a fungicide that works in a different way. Therefore, it is important to avoid one-sided use of fungicides with the same mode of action. In addition, in plant production, one should use integrated pest management (IPM) to reduce the need for fungicides (and other pesticides).

Contacts

What is One Health?

One Health is an integrated, unifying approach that aims to sustainably balance and optimize the health of people, animals, and ecosystems. It recognizes the health of humans, domestic and wild animals, plants, and the wider environment (including ecosystems) are closely linked and interdependent. The approach mobilizes multiple sectors, disciplines, and communities at varying levels of society to work together to foster well-being and tackle threats to health and ecosystems, while addressing the collective need for healthy food, water, energy, and air, taking action on climate change and contributing to sustainable development.

(The definition is developed by WHO, FAO, WHOA, and UNEP)

NavAzole

NavAzole (Navigating the threat of azole resistance development in human, plant and animal pathogens in Norway) is a five-year project led by the Norwegian Veterinary Institute, which started in 2021. The project is funded by the Research Council of Norway (NFR), and is a collaboration between the Norwegian Veterinary Institute, NIBIO, Oslo University Hospital, Norwegian University of Life Sciences, Norwegian Agricultural Advisory Service, Norwegian Food Safety Authority, Cancer Society, BAMA Gruppen AS and Radbound University Nijmegen Medical Center. The project aims to map and understand the development of azole resistance in Norway, through studies of isolates from three fungal species (Aspergillus fumigatus, Zymoseptoria tritici and Parastagonospora nodorum) from various environments. Furthermore, the project will establish methods, networks and routines for diagnostics and monitoring of azole resistance in Norway.

Contacts