EU clears the way for CRISPR crops – Norway expected to follow

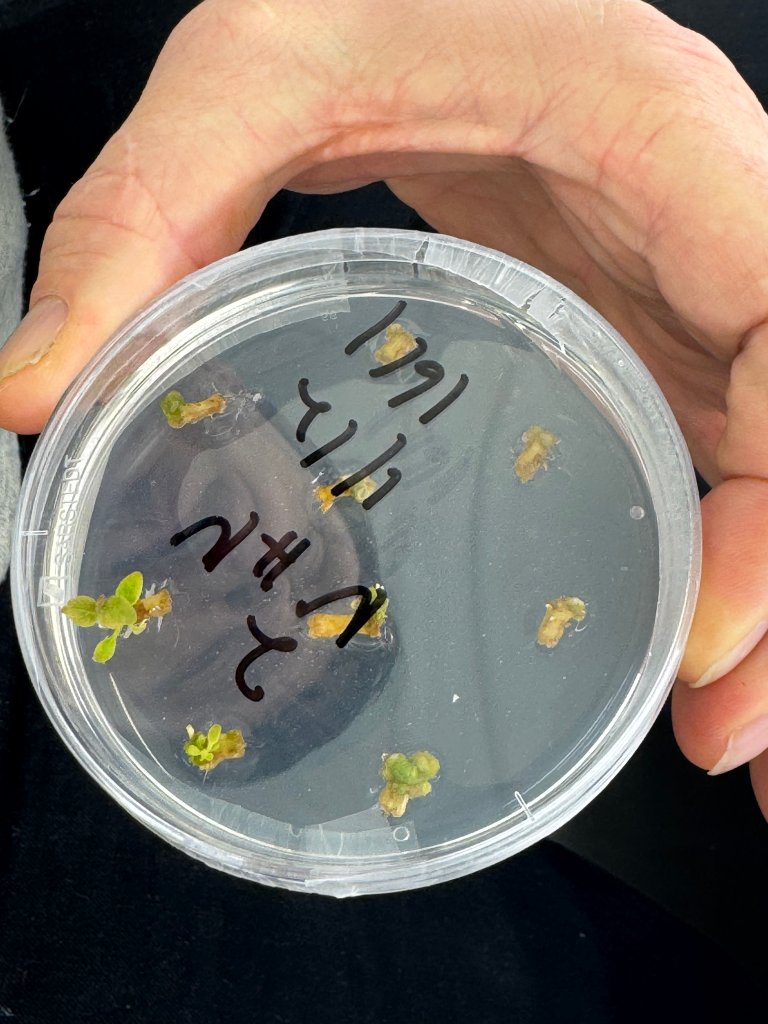

Researcher Tage Thorstensen and his team at NIBIO developed the world’s first CRISPR-edited iceberg lettuce with increased resistance to rot fungi. New EU regulations may now make it easier to test the lettuce in field trials and eventually bring it to consumers. Photo: Siri Elise Dybdal

The European Union has approved new rules that make it easier to use gene editing in food crops. The decision paves the way for Norway to allow the cultivation of gene-edited plants with improved resistance to disease.

NIBIO researcher Tage Thorstensen and his team are behind both Norway’s first gene-edited food plant and the world’s first CRISPR-edited iceberg lettuce with increased resistance to rot fungi. However, strict regulations have prevented further field testing and market use. Now, the EU has adopted a temporary decision on new rules that make it easier to use gene-editing tools like the CRISPR “gene scissors” in plants, without them automatically being classified as GMOs (genetically modified organisms). This regulatory easing in the EU falls under the EEA Agreement and will therefore also affect Norway – and the research team at NIBIO.

Norway must follow suit

CRISPR technology makes it possible to selectively switch off genes that make a plant susceptible to disease and stress. It can also be used to deactivate genes that produce unwanted substances.

More resilient plants can, among other things, reduce the need for pesticides in agriculture. CRISPR technology differs from GMO methods in that it involves targeted gene editing without introducing foreign genes, whereas GMOs traditionally involve inserting genes from other species into the plant.

“After more than ten years of discussions, the EU has made a temporary decision that gene-edited plants should be regulated under the same legislation as other plants,” says Tage Thorstensen. who is pleased by the development. He notes that the news of the legislative change came ten years to the day after he wrote an op-ed about the possibilities of using CRISPR in the newspaper Dagens Næringsliv.

“It was a funny coincidence,” he comments.

The legislative change still must go through a few more steps in the EU before final adoption. On 28 January, the European Parliament’s Committee on the Environment, Public Health and Food Safety (ENVI) voted in favour of the decision, bringing the final legal amendment expected in April one step closer. After that, it may take a couple of years before the law is implemented in practice.

The new rules apply to plants where gene editing has not led to the introduction of foreign DNA, and where the changes correspond to mutations that could also arise naturally.

“Such plants will no longer be regulated more strictly than other plants,” says Thorstensen.

No labelling required

A key requirement has been transparency around patents. After lengthy discussions on patents and labelling, patenting has been allowed – but patents must be registered in a database and be licensable on equal and fair terms. It will not be permitted to patent traits or sequences that occur naturally.

“Plants that are gene-edited can now be patented, but since the licences must be fair, this means that no one will be able to block others from using the technology,” says Thorstensen.

“This makes CRISPR technology accessible to farmers and breeders, while also providing incentives for biotechnology companies to invest in developing new gene-edited varieties.”

Gene-edited products will not have to be labelled in shops, but seeds must be labelled so that producers can make informed choices.

“Consumers will therefore not encounter a ‘gene-edited carrot’ on the supermarket shelf. This clarification has been important.”

“Many countries have waited a decade for this decision. It is crucial for further commercialisation and for being able to put the technology into practical use,” says the NIBIO researcher.

He is now eagerly awaiting to see how quickly the new rules will be implemented.

“In the EU, such processes take time – often one to two years before regulations enter into force. England already introduced similar regulations last year. It is uncertain how long it will take for Norway to follow, but it should happen quickly after the EU, since a lack of coordination would in practice become a trade problem. The regulations therefore need to be coordinated,” Thorstensen points out.

Nevertheless, he hopes that it may already be possible to plant the gene-edited lettuce in a regular field this year as part of the research.

“We are planning field trials. The regulations are so strict that the Norwegian Environment Agency denied us permission to bring chopped CRISPR-edited lettuce to Arendalsuka last August. But an amendment to the Gene Technology Act on 1 October has made it somewhat easier to carry out field trials, even though Norway still lags far behind the EU.

“So the goal is to conduct field trials with gene-edited lettuce already this summer!”

Working with key Norwegian food crops

NIBIO is now building up CRISPR infrastructure, and new growth chambers are already completed.

“The facilities are in place for the entire development process to take place internally: molecular biology work such as cloning and editing genetic material in the lab, gene-edited cell clusters in dishes, and small plants in growth chambers,” Thorstensen explains.

Going forward, the researchers will continue developing new lettuce varieties that are more tolerant to fungal diseases. Such diseases can lead to major yield losses with significant economic consequences for Norwegian producers.

“The lettuce project aims to develop alternatives to today’s varieties. We have succeeded in making plants more resistant to Sclerotinia rot. That shows it can be done. In a new project, we will now also work on diseases such as downy mildew and lettuce anthracnose. I find that more farmers have become positive. The same applies to an increasing number of companies in the food production value chain,” he says.

“There is also great interest in NIBIO’s work on gene editing in potatoes. Potatoes are a very important crop – a staple food and relatively easy to work with compared to many other species. Among other things, we are working to develop Norway’s first late blight-resistant potato,” the researcher explains.

Gene-edited apples that do not turn brown and that are more resistant to apple scab are another important project.

“Apples are Norway’s most widely grown fruit, with 12,000–19,000 tonnes annually. Apple scab, caused by the fungus Venturia inaequalis, can lead to major yield losses in susceptible varieties, while restrictions on pesticides and consumer demands for fewer chemicals make disease control challenging. At the same time, up to 40 per cent of apples end up as food waste, often because they turn brown after cutting,” Thorstensen explains.

A leading centre of expertise

He describes the CRISPR team at NIBIO as small but dedicated, consisting of master’s students, engineers and researchers.

“The goal is to build a strong centre of expertise and a national hub in Norway. To succeed, resources must be invested.”

“Collaboration between companies and research actors is also crucial to bringing products forward. If something is to reach the market, it must go through companies, just as all drug development, for example, takes place through commercial actors.”

“The regulatory framework has made this more realistic, and now gene editing can actually make a difference in Norwegian food production,” he believes.

Precaution

Over the past ten years, Thorstensen has often had to defend CRISPR technology. He says opponents of gene editing frequently refer to the precautionary principle and unforeseen mutations.

“The intention is good, but a lack of understanding of genetics limits the debate,” he believes.

The NIBIO researcher points out that traditional breeding already involves unknown mutations, and that garden and food plants accepted today are highly bred and contain far more unknown genetic changes than those introduced through gene editing.

“In addition, entirely new food plants such as broccolini and Brussels sprouts are introduced to the market. These contain completely new and unknown gene combinations and mutations without any risk assessment. These are harmless mutations, but it is strange that opponents of gene editing are not concerned about all these unknown mutations when they are so worried about a single targeted mutation introduced through CRISPR editing.”

“The precautionary argument has been used for many years, which is why it was a great relief that the EU finally made this decision, even if it took time,” he notes.

A tool in the fight against disease and food waste

Thorstensen does however stress that gene editing is not a solution to everything, but an important tool in addressing climate change and increasing disease pressure:

“It requires a supportive regulatory framework, risk capital, research funding, and not least consumer acceptance to get a gene-edited plant to market. With gene editing, targeted improvements to plant traits can be made much faster and more efficiently than through conventional breeding, where plants must be crossed over several generations to achieve the desired trait.”

“Combined with artificial intelligence, which can be used to select genes, streamline editing and predict effects, the use of gene editing in developing more sustainable plants will progress much faster than traditional breeding.”

This will become increasingly important for adapting crops to climate change, reducing food waste and lowering the need for pesticides, he believes.

Must become more forward-looking

The NIBIO researcher points out that deregulating gene-edited plants also has major trade policy implications. The EU has long been lagging the US and China in this area.

“To remain competitive, the EU must become more forward-looking. I hope implementation happens quickly. It has not been possible to commercialise CRISPR products, and private investors stayed away. Now things are different. As mentioned, we see that major actors in the value chain are very interested. The regulatory changes have opened new opportunities.”

Thorstensen also highlights the international significance:

“Diseases in coffee, cocoa, citrus trees and grapevines are increasing, and in many parts of the world – especially in Africa – there are limited opportunities to grow food safely due to drought and disease. Gene editing can be an important contribution to securing food supply and sustainable production.”

“Gene editing is not the solution to everything, but compared to what is already accepted, it is a very important tool. So far, Norway has been able to buy its way out of problems related to food production, but that will not be sufficient in the long term,” Thorstensen concludes.

Contacts

What is CRISPR?

CRISPR is a kind of “gene scissors” that can remove, add or replace pieces of DNA as desired in all types of living organisms. There is hope that the tool can help address challenges related to food security, climate change and sustainability.

What are the new EU rules?

On 3 December 2025, the EU reached a preliminary agreement that plants modified with genes from the same species, and which could have arisen through natural mutations, should no longer be regulated as genetically modified (GMO) plants, but as traditionally bred plants. In a vote in the European Parliament’s Environment Committee on 28 January 2026, the content of the agreement was approved. A final decision is expected in April 2026.

Are there any requirements for CRISPR plants?

At the request of Parliament, agreement has been reached on a list of undesirable traits that are not permitted in gene-edited plants. Gene edits that could lead to increased environmental or health risks cannot be approved, such as traits that could make a plant more invasive or unpredictable in nature. Traits that lead to resistance against insect pests or pesticides are also not permitted.

Clear distinctions will still be maintained to ensure that organic agriculture is not mixed with gene-edited plants.

Contacts

.jpg?quality=60)